Immersive theatre: 12 legal factors to consider

Immersive theatre is one of the fastest-evolving sectors of the performing arts and with great possibility also comes high risk of potential pitfalls. Music and entertainment lawyer Irving David outlines some of the biggest legal factors for producers to think about when staging this kind of work

Immersive theatre has evolved from an experimental curiosity into an established part of the live performance landscape. Producers are now investing in installations that place audiences inside the action, often using technology, close interaction and multi-room environments. This expands artistic scope, but also increases the legal, licensing and operational work required to support it.

Punchdrunk’s long-running Sleep No More at the McKittrick Hotel in New York remains the benchmark for large-scale, free-roaming immersive work. Having run from 2011 to 2025, it spanned multiple floors filled with design, sound, choreography and highly controlled audience movement. Its longevity underscores a central point: the more elaborate the installation, the more producers must plan for maintenance, rights management and ongoing renewal of creative assets.

Clear rules and trained supervision are essential where audience proximity is central to the experience

A significant UK example is the current revival of Cabaret at the Kit Kat Club, which has transformed the Playhouse Theatre into a reimagined nightclub. Audiences move through staged rooms before taking seats at cabaret-style tables. Performers circulate among the audience and the experience begins long before curtain-up. It demonstrates how a mainstream musical can adopt immersive framing while retaining a structured auditorium.

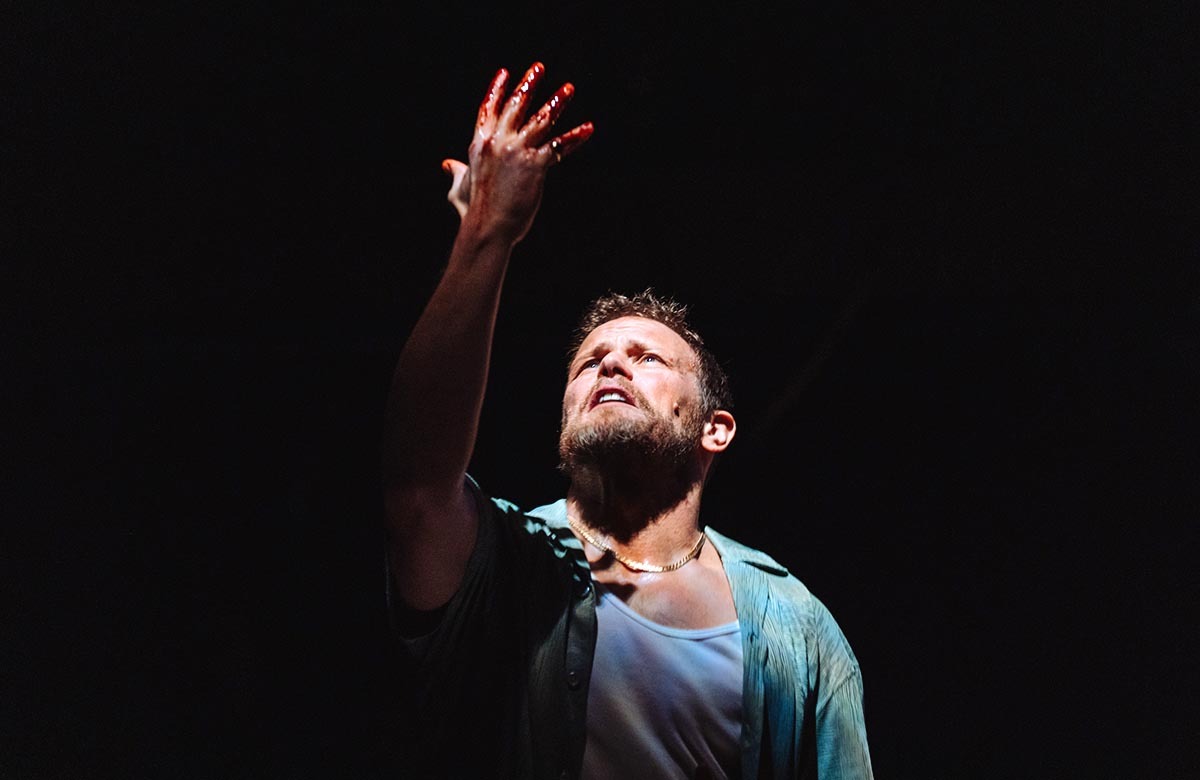

Another recent UK example was the Royal Shakespeare Company’s close-quarters Macbeth, which concluded its run at the Other Place in Stratford-upon-Avon in December. Although not free roaming, it placed audiences in unusually close proximity to the actors, using direct presence, confined space and altered staging to reshape the audience’s relationship to the action.

Continues...

Once a production invites any degree of closeness or informal participation, producers must consider performer rights, safeguarding and clarity around the audience’s role. If these issues are not addressed in advance, productions expose themselves to reputational damage, performer complaints and, in serious cases, regulatory or employment claims.

There are well-publicised examples of how immersive formats can create welfare and boundary challenges. In Punchdrunk’s New York production of Sleep No More, performers have spoken in the media about being touched inappropriately by audience members in the unstructured environment, prompting the company to restate and reinforce its audience conduct rules. In London, You Me Bum Bum Train has attracted public discussion about performer welfare and the need for clear opt-out and reporting mechanisms for its volunteer cast. These cases illustrate why clear rules and trained supervision are essential where audience proximity is central to the experience.

From a legal perspective, here are the top considerations for producers seeking to stage immersive theatre:

1. Rights and licensing

Immersive work broadens the rights landscape beyond that of a conventional production. The principles remain familiar, but the volume and interdependence of rights increase. For example, a single immersive room might combine a commissioned soundscape, licensed recorded music, a projection artwork, bespoke costumes and scripted performer interaction. Each of those elements carries separate copyright, neighbouring rights and moral rights, all of which must align if the production is to be reused, toured or digitally captured.

2. Music and sound

Installations often combine original compositions, licensed recordings, ambient layers and digital or AI-assisted sound generation. Producers must secure licences for each element and ensure that no assets are used as training data for AI systems without permission.

3. Design and scenography

Sets, props, masks, costumes and lighting designs remain subject to copyright, but immersive work typically involves more designers and bespoke environments. Work-for-hire clauses and restrictions on reuse help reduce risk.

4. Performer rights and interaction

Closer contact requires clear boundaries. Rules around touch, movement, photography and recordings must be defined. Performers may need stronger contractual protection where audience behaviour is less predictable. In the UK, Equity agreements increasingly include specific provisions for immersive work, covering safeguarding, consent and limits on physical interaction.

5. Technology and data

RFID wristbands (used in immersive theatre to unlock doors, for example), mobile apps and tracking systems are increasingly used to manage flow or personalise scenes. These tools collect data, so producers must comply with data protection law and ensure responsible handling by technology partners.

6. Model training exclusions

Many creators now require explicit clauses preventing their work from being used for AI training unless they give separate written consent. These clauses appear across music, design, photography and performance contracts and should be treated as standard.

Continues...

7. Production and operational demands

Immersive productions require a different approach to planning and logistics. Unlike conventional shows, sets, technology and performers must operate continuously across multiple spaces, often for many hours a day, with no single curtain-up moment. This requires staggered staffing, constant technical support and detailed contingency planning to keep the experience safe, coherent and commercially viable.

8. Higher upfront costs

Multi-room installations demand more infrastructure, technology and bespoke design. Producers must commit to higher capital expenditure before opening. Extended runs and additional revenue streams can offset this if the installation is stable and well managed.

9. Venue licensing

Unusual layouts may fall outside standard theatre permissions. Producers may need approvals relating to movement, fire safety, capacity, darkness and late-night operation. Early dialogue with licensing authorities avoids last-minute changes.

10. Audience behaviour and safeguarding

Immersive environments reduce predictability. Audiences may move unexpectedly, cross boundaries or become disoriented. Staff members require training to manage behaviour and safeguarding risks. Clear communication with audiences is essential.

11. Commercial models

These productions can support extended runs, brand partnerships, merchandise and digital extensions. This requires detailed rights allocation and transparent revenue sharing, with accounting arrangements covering both physical and digital income.

12. Technology partners

Immersive work depends on reliable technology. Contracts must address data ownership, support obligations, system continuity and liability. Some early immersive shows faltered when technology suppliers withdrew or shifted focus.

So where is immersive work heading next? Three developments are shaping the next phase.

The first is adaptive content. Digital systems can adjust lighting, sound or narrative elements based on individual movement. This increases engagement but raises questions about authorship, control and system maintenance.

Continues...

The second development is AI-assisted design. Creative teams use AI tools to generate textures, images and prototypes. This accelerates design, but requires clarity about copyright ownership and compliance with training data requirements.

And the third factor is digital venue replicas. Digital twins of theatres support remote planning, virtual rehearsals and online engagement. These replicas carry their own rights and need agreements that define how the physical venue is represented.

Immersive and immersive-adjacent productions are now firmly established within the theatre ecosystem. Artistic potential is high, but so are the demands. Rights are broader, technology is deeper and operational risk is higher.

Immersive theatre is strongest when artistic freedom and disciplined governance move together

Producers who succeed will be those who combine ambition with structured planning. Clear contracts, firm rights allocation, reliable technology governance and early operational preparation are essential.

Immersive work thrives on unpredictability, but the frameworks supporting it must be precise. The next decade will see deeper digital integration, more hybrid formats and continued blending of theatre, installation art and interactive entertainment. Organisations that plan now for the rights and technical landscape will be best placed to lead the next phase.

From my own work advising creators, producers and arts organisations, one theme continues to stand out: immersive theatre is strongest when artistic freedom and disciplined governance move together. Companies that treat rights, data, design ownership and performer protection as core creative infrastructure rather than administrative burden will shape the next wave of work.

Opinion

Recommended for you

Advice

Recommended for you

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99

Irving David

Irving David