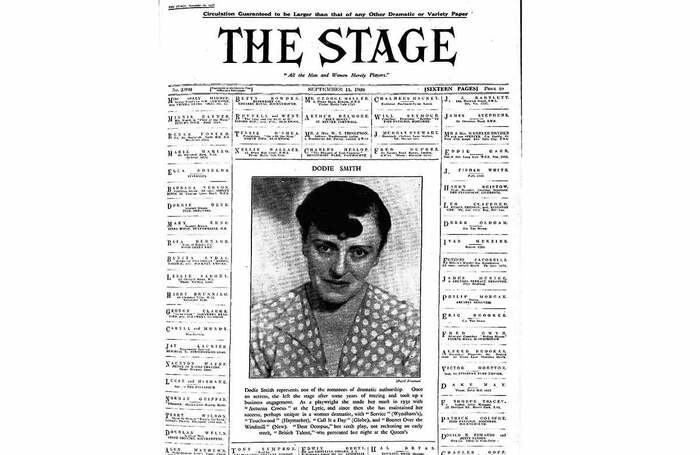

‘Little Dodie Smith’ – one of the most successful female writers of her time

Best known for novels The Hundred and One Dalmatians and I Capture the Castle, Dodie Smith was also one of interwar Britain’s most successful dramatists. Julia Rank looks back at her career, ahead of the NT’s revival of Smith’s 1938 play Dear Octopus

In Dodie Smith’s partially autobiographical 1965 novel The Town in Bloom, the aspiring actor heroine is known only as Mouse and has recently arrived in London having been raised by a progressive feminist aunt. She has no acting talent but is blessed with an abundance of winsomeness and not a trace of imposter syndrome – much like Smith herself. As biographer Valerie Grove explains in her 1996 book, Smith, throughout her life (she died in 1990 at the age of 94), thought of herself as ‘Little Dodie Smith’, a precocious and uninhibited child who never grew up.

However, there was nothing diminutive about Smith’s stature in interwar theatre – she became one of Britain’s most successful dramatists and her 1935 work Call It a Day became, at the time, the longest-running play by a female writer.

Smith grew up in Edwardian Manchester, where professional and amateur theatre was at the centre of cultural and social life. She spent her childhood as the adored only child of a widowed mother living with theatre-mad relatives. She attended RADA and while she never approached stardom as a performer, she enjoyed more success than her aforementioned literary self-portrait would suggest.

Smith retired from acting in 1922 to take a job in the toy department in Heal and Son’s department store. When she wrote her first play Autumn Crocus almost a decade later in 1931, it was greeted with the headline “Shopgirl writes play”, but a string of commercial and critical successes put short shrift to such condescending attitudes.

Just as she employed tropes in her novels, “Smith knew how to entertain audiences; she uses tropes and comments on them”, observes actor Billy Howle, who is starring in the National Theatre’s current revival of Smith’s 1938 play Dear Octopus.

Continues...

Emily Burns’ production, which begins previews in the Lyttelton this week, marks the first revival of Dear Octopus since the 1980s: like many playwrights of her generation, Smith’s work fell out of favour following the Second World War and the rise of the Angry Young Man, and fell further still following the demise of the repertory system.

In recent years, Smith stagings have included a musical adaptation of her coming-of-age classic I Capture the Castle, which premiered at Watford Palace Theatre in 2017, and a modernised musical version of her children’s novels The Hundred and One Dalmatians (probably better known in the form of two Disney adaptations) played at the Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre in 2022 and tours this summer, although it has little connection with Smith the 1930s playwright.

Dear Octopus – which, in 1938, was her sixth play produced in seven years – centres around a large family, who assemble for the golden wedding anniversary of parents Dora and Charles Randolph, played in this production by Lindsay Duncan and Malcolm Sinclair.

Burns, whose credits include Richard Bean’s Jack Absolute Flies Again, first read the play about five years ago on National Theatre associate Ben Power’s recommendation, and revisited it when she was looking for a play to stage in the Lyttelton. “I found it so singular in the way it explores family and returning home. When we did a cold read, the play spoke for itself.”

Inspired by Thea Sharrock’s 2010 production of Terence Rattigan’s After the Dance, Burns immersed herself in plays from the late 19th and early 20th century. “It was the birth of naturalism and the director working in an artistic capacity rather than as an administrator,” she explains.

‘Smith knew how to entertain audiences’ – Billy Howle, actor

Howle plays Nicholas, the youngest sibling. “He’s a bachelor in his 30s and wouldn’t be under as much pressure as an unmarried woman but it’s still quite noticeable to the rest of his cohort. He works in advertising, a newfangled kind of job then, and comes across as bit of a man-about-town but he isn’t really. He’s taken under the wing of Edna [played by Pandora Colin], the widow of his brother, Peter, who died in the First World War when Nicholas was a child. The dynamic between them is really interesting and the text is so malleable.”

The role was originated by no less than John Gielgud, fresh from playing all the leading Shakespearean roles, and who originally offered to direct. This isn’t the first time Howle has followed in Gielgud’s footsteps, having been inspired by the theatrical titan when he played Hamlet at the Bristol Old Vic in 2022. “I’ve always looked up to Gielgud, and actors with that kind of gravitas, since I was quite young,” he says. “I don’t feel any pressure, I just get on with it, which I think he would approve of.”

Continues...

For Burns, working with a large ensemble means that “you have a group of unselfish performers in which no one thinks that they’re the main character and the focus is always shifting. With family gatherings, everyone puts on a brave face and best behaviour, at least at first. Everyone who sees the play will find a dynamic that feels familiar. It’s a family that’s been apart and suffered losses but they’re now coming back together and trying to celebrate. At the next such gathering, they likely won’t all still be there. As I get older, that kind of bittersweetness is more and more of a key thread that I’m pulled by.” Howle agrees: “People are always going to relate to themes of ageing, grief and loss.”

He adds: “The themes are really layered but Smith could also write a seriously good gag – the text is littered with them.”

Smith’s diaries and memoirs show that she never lacked confidence. As Burns says: “When Smith wrote her first play, she was having an affair with Ambrose Heal, her boss, but once she became successful in her own right, she lost interest in the relationship. Later, her husband Alec Beesley became her manager and devoted himself to her career. She was such a significant female playwright and her archive is full of letters from other writers expressing admiration and envy for the way she could evoke moods and feelings – and especially the way she achieved it with such a light touch.”

Dear Octopus runs at the National Theatre from Feb 7 to March 27. For full details visit: nationaltheatre.org.uk

Discover theatre history...

If you’d like to read more stories from the history of theatre, all previous content from The Stage is available at the British Newspaper Archive in a convenient, easy-to-access format. Please visit: thestage.co.uk/archive-virtual

Opinion

Opinion

Most Read

Across The Stage this weekYour subscription helps ensure our journalism can continue

Invest in The Stage today with a subscription starting at just £7.99